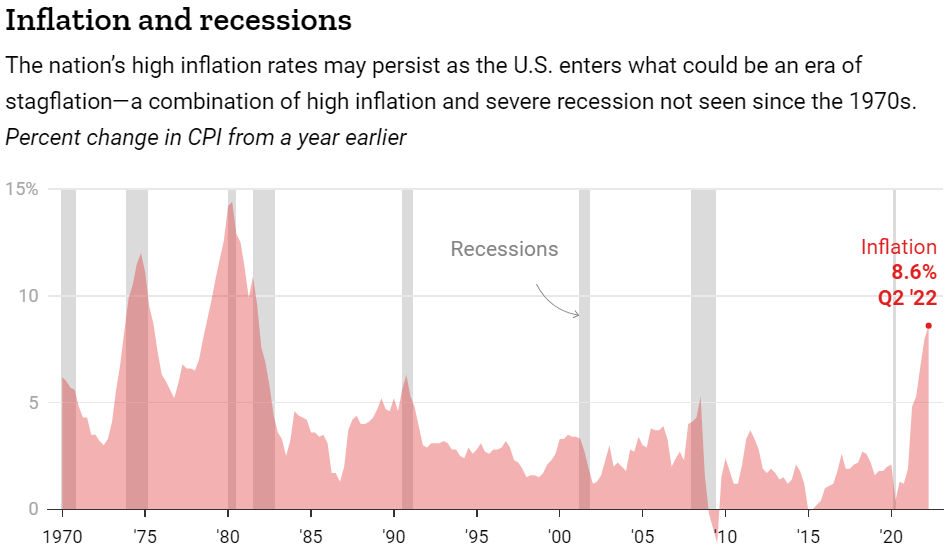

In recent times, the term stagflation has made a surprising comeback in economic discussions, driven by a resurgence of inflation. Over the past year, inflation has been on a sharp rise, fueled by a complex interplay of both demand and supply factors. This inflationary trend may not be a transient phenomenon; rather, it could signal the end of the Great Moderation era of the past three decades, ushering us into a new era characterized by what we might call “Great Stagflationary Instability.”

Until 2021, inflation, which represents the increase in prices year to year, had been largely below the target of 2% set by central banks in advanced economies. Typically, inflation is associated with robust economic growth. When aggregate demand for goods, services, and labor is high, bolstered by positive sentiment, optimism, and accommodating monetary and fiscal policies, we witness economic growth surpassing its potential, accompanied by higher-than-target inflation. Firms can raise prices as demand outpaces supply, and workers enjoy increased wages due to low unemployment rates. Conversely, during economic downturns, demand slackens, leading to low inflation or even deflation as consumer spending declines. Stagflation, on the other hand, is a term used to describe a scenario where high inflation coincides with economic stagnation or even recession.

Sometimes, economic shocks stem from the supply side, such as an oil-price shock or spikes in food and commodity prices. These supply-side shocks lead to increased energy and production costs, which, in turn, impede growth in countries reliant on imported fuel or food. Consequently, we witness economic slowdowns or even recessions while inflation continues to surge. If policymakers respond to such negative supply shocks with loose monetary and fiscal policies, essentially stimulating demand for goods and labor to counteract the growth slowdown, it can inadvertently fuel inflation. The outcome is a persistent form of stagflation: a recession accompanied by high inflation.

The 1970s serve as a historical example of a decade plagued by stagflation. Two major oil shocks and a flawed policy response led to high inflation and recession. The first shock occurred when the oil embargo was imposed on the U.S. and the West following the 1973 October War in the Middle East. The second was triggered by the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran. Both events resulted in soaring oil prices, causing inflation and recessions in Western economies heavily reliant on oil imports. The inflationary spiral was exacerbated by the inadequate policy measures to contain it. It took a painful double-dip recession in 1980 and 1981-1982, during which then-Fed Chairman Paul Volcker raised interest rates to double-digit levels, to finally quell inflation.

The Great Moderation followed the stagflation of the 1970s and early 1980s. This period was marked by low inflation in advanced economies, stable and robust economic growth with brief and shallow recessions, and falling bond yields thanks to decreasing inflation. A key factor behind this extended period of low inflation was the adoption of credible inflation-targeting policies by central banks, along with relatively conservative fiscal policies. However, more critical than demand-side policies were the numerous positive supply shocks that increased potential growth and reduced production costs, helping keep inflation in check.

During the era of hyper-globalization that followed the Cold War, emerging-market economies like China, Russia, and India became integrated into the global economy, supplying low-cost goods, services, energy, and commodities. Mass migration from the Global South to the Global North kept wage pressures in check in advanced economies, technological innovations lowered production costs, and relative geopolitical stability allowed for efficient allocation of production. This combination of factors contributed to the Great Moderation.

However, cracks in the Great Moderation emerged during the 2008 global financial crisis and were exacerbated by the 2020 COVID-19 recession. Although these crises led to severe economic downturns and financial strains, inflation remained subdued initially, thanks to demand-side shocks. Loose monetary, fiscal, and credit policies prevented deflation from taking hold.

The current situation is different. Inflation has been rising since 2021, prompting debates among economists, policymakers, and investors. Questions abound: What is the nature of this inflation? How persistent will it be? Is it a result of loose monetary and fiscal policies or negative aggregate supply shocks? Will central banks’ efforts to combat inflation result in a soft landing or a hard landing? If it’s the latter, will the recession be brief or severe? Will central banks stay committed to fighting inflation, or will they back down, ushering in a new era without the Great Moderation?

The first question about the longevity of rising inflation seems to have been settled, with the “Team Persistent” viewpoint prevailing over the “Team Transitory” camp, which included most central banks and fiscal authorities.

The second question pertains to whether inflation has been primarily driven by bad policies, such as excessive aggregate demand resulting from overly loose monetary, credit, and fiscal policies, or if it’s mainly due to unfavorable supply-side factors, including initial COVID-19 lockdowns, supply chain disruptions, labor supply shortages in the U.S., the impact of Russia’s Ukraine war on commodity prices, and China’s zero-COVID policy. While both demand and supply factors have played a role, supply-side factors are now acknowledged as increasingly influential. This matters because supply-driven inflation is stagflationary and raises the risk of a hard landing when monetary policy is tightened.

This brings us to the third question: Will the tightening of monetary policy by major central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve result in a hard landing (recession) or a soft landing (a growth slowdown without a recession)? Initially, most central banks and Wall Street were on the “Team Soft Landing” side. However, the consensus has shifted rapidly, and even Fed Chair Jerome Powell has acknowledged the possibility of a recession, stating that a soft landing would be “very challenging.”

A model used by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York suggests a high probability of a hard landing, and the Bank of England shares similar views. Several prominent Wall Street institutions now consider a recession as their baseline scenario. In the past six decades of U.S. history, whenever inflation has exceeded 5% while the unemployment rate has remained below 5%, any attempt by the Fed to curb inflation has resulted in a hard landing. Thus, a hard landing appears more likely than a soft one in the U.S. and other advanced economies.

The fourth question pertains to whether we are already in a recession. Forward-looking indicators of economic activity and business and consumer confidence in both the U.S. and Europe are trending downward. While the U.S. experienced two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth in the first half of the year, strong job creation initially kept us from a formal recession. However, as the labor market weakens, a recession by year’s end appears likely in the U.S. and other advanced economies.

Given the increasing consensus on the likelihood of a hard landing, a fifth question emerges: Will this forthcoming recession be mild and short-lived, or will it be more severe, marked by deep financial distress? Some still argue for a shallow and brief recession, claiming that today’s financial imbalances are not as severe as those preceding the 2008 global financial crisis, suggesting a low risk of a recession coupled with a severe debt and financial crisis. However, this view may be overly optimistic.

There are compelling reasons to believe that the next recession will involve a severe stagflationary debt crisis. Global debt levels, both public and private, have surged from

200% of global GDP in 1999 to 350% today. Under these conditions, the rapid normalization of monetary policy and rising interest rates could drive heavily leveraged households, corporations, financial institutions, and governments into bankruptcy and default.

When dealing with stagflationary shocks, central banks must tighten their policy stance as the economy heads toward recession. This situation differs from the global financial crisis or the early months of the pandemic when central banks could aggressively ease monetary policy in response to falling demand. Fiscal expansion options are also limited this time, and public debts are becoming unsustainable.

Furthermore, as higher inflation is a global phenomenon, most central banks are tightening simultaneously, increasing the likelihood of a synchronized global recession. Already, bubbles are deflating across various asset classes, including public and private equity, real estate, housing, meme stocks, cryptocurrencies, SPACs, bonds, and credit instruments. Real and financial wealth is declining, while debt and debt-servicing ratios are rising.

Consequently, the next crisis will not resemble its predecessors. In the 1970s, stagflation coexisted with no major debt crises because debt levels were low. After the 2008 crisis, there was a debt crisis followed by low inflation or deflation due to the credit crunch causing a demand shock. Today, we face supply shocks in a context of much higher debt levels, setting the stage for a combination of 1970s-style stagflation and 2008-style debt crises—a stagflationary debt crisis.

This leads to the final question: How will financial markets and asset prices, particularly equities and bonds, perform in an era of rising inflation and the return of stagflation? It is highly likely that both components of a traditional asset portfolio—long-term bonds and U.S. and global equities—will experience significant losses. Rising inflation will drive up bond yields and reduce bond prices. Equities will also suffer as rising interest rates negatively impact firm valuations. In 1982, during the peak of stagflation in the ’70s, the price-to-earnings ratio of S&P 500 firms had plummeted to 8, compared to the current level close to 20. Consequently, a prolonged and severe bear market is a real risk. For the first time in decades, a 60/40 portfolio of equities and bonds has incurred substantial losses in 2022 as bond yields surged and equities entered a bear market.

Investors need to consider assets that can serve as hedges against inflation, political and geopolitical risks, and environmental damage. These may include short-term government bonds and inflation-indexed bonds, gold and other precious metals, and real estate that can withstand environmental challenges.

In summary, the decade ahead may unfold as a Stagflationary Debt Crisis unlike anything witnessed before. The convergence of persistent and recurring negative supply shocks with loose monetary, fiscal, and credit policies may result in a period combining the worst aspects of the 1970s stagflation and the post-global financial crisis period marked by debt crises. As the landscape evolves, investors will need to navigate these challenges with a keen eye on asset protection and diversification.